Allergies vs Food Sensitivities: Tips, Testing, and Safer Eating

Understand food allergies vs sensitivities, test options, elimination plans, and daily routines that lower symptom flares and reduce hidden exposure risks.

11 Min Read

Food allergy, intolerance, and sensitivity differences are not semantics

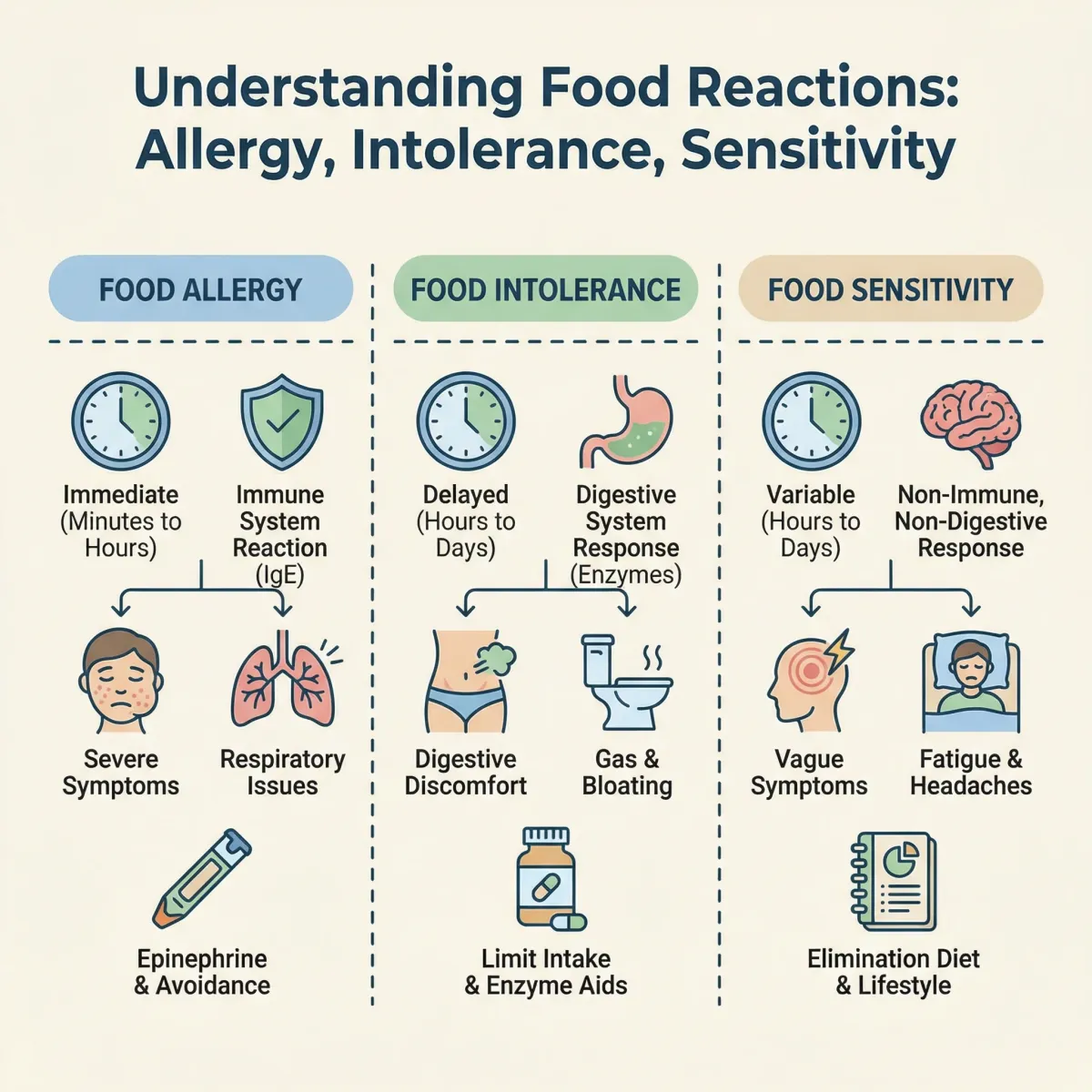

People often use the terms “food allergy,” “food intolerance,” and “food sensitivity” interchangeably. That is understandable in daily conversation, but medically these labels point to different mechanisms and different levels of risk. A true food allergy is an immune reaction to a food protein. It can involve rapid symptoms and, in some cases, anaphylaxis. U.S. regulators and clinicians frame this category as a high-priority safety issue because accidental exposure can be dangerous. The FDA’s food-allergy guidance is built around this risk model.

Food intolerance usually means symptoms caused by digestion, absorption, or biochemical processing rather than a classic immune allergy pathway. Lactose intolerance is the common example. You may feel uncomfortable, but the risk profile is very different from a peanut allergy that can progress quickly. “Food sensitivity” is often used as an umbrella term for non-allergic reactions where symptoms are real but mechanisms vary and are sometimes uncertain. This is one reason patients get mixed advice: one clinician may prioritize GI differentials, while another prioritizes allergy exclusion first.

For practical decision-making, you do not need perfect mechanistic certainty on day one. You need triage clarity. First, rule out dangerous allergy patterns. Then structure a focused investigation for lower-risk but persistent symptoms. If your symptom pattern includes digestive instability, bloating, or stool changes after a broader diet shift, it can help to compare this guide with evidence-informed gut-health resources like probiotic foods and supplements basics so you do not over-attribute every symptom to one ingredient.

| Category | Main mechanism | Typical timing | Risk level | Best first step |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food allergy | Immune response to food protein | Minutes to a few hours (often rapid) | Can be severe | Allergy evaluation and emergency planning when indicated |

| Food intolerance | Digestive or metabolic limitation | Hours to one day | Usually non-life-threatening | Targeted intake adjustment and symptom tracking |

| Food sensitivity (umbrella term) | Mixed or unclear pathways | Variable, sometimes delayed | Variable | Structured elimination/rechallenge with clinician input |

A useful rule: if symptoms include throat tightness, breathing difficulty, lightheadedness, widespread hives, or rapid progression after eating, treat that as possible allergy and seek immediate care. If symptoms are mostly chronic GI or skin flares without rapid escalation, the workflow is different and usually less urgent, but still requires structure.

Why timing of symptoms can be misleading

Timing is one reason people feel confused. Not all reactions happen at the table. Some happen later in the day, overnight, or the next day, which makes cause-and-effect look random. Delayed patterns are especially common in non-IgE pathways and in conditions where total dietary load, stress, sleep disruption, and gut motility all interact. This does not mean symptoms are imaginary. It means your “signal” is noisy.

Noise creates two common mistakes. First, people blame the last food they ate and miss the cumulative pattern. Second, people become so restrictive that nutrition quality drops, then feel worse and interpret that decline as another new sensitivity. A better approach is to track timing windows: 0 to 2 hours, 2 to 8 hours, and 8 to 48 hours. Over several weeks, this framework can reveal whether specific foods, food groups, or meal patterns are more likely triggers.

Clinical overviews such as the NIH/NCBI StatPearls review on food allergy and patient resources from major systems like Mayo Clinic emphasize symptom pattern, not single isolated episodes. Pattern beats memory. Memory is biased by fear, recency, and stressful events.

If you are uncertain whether your response pattern is connected to fermented foods, prebiotics, or probiotics, this companion guide on how to know probiotic supplements are working can help separate expected adjustment effects from true intolerance signals.

Common trigger foods and hidden exposures are where most setbacks happen

Most people know the major allergen categories. Fewer people know where hidden exposure happens: seasoning blends, sauces, deli counters, bakery cross-contact, shared fryers, supplement excipients, and inconsistent restaurant prep. Even motivated households underestimate how often small exposures accumulate through “minor” ingredients.

For regulated allergens in packaged foods, label reading is non-negotiable. Start with the allergen statement, then read the ingredient list anyway because formulation changes do happen. The FDA’s current allergen labeling resources are useful as a baseline, but your real-world safety depends on daily systems, not one-time education.

When symptoms look more like intolerance than acute allergy, hidden exposures can still matter through cumulative dose. People may tolerate a small amount in one setting but not when repeated across multiple meals. This is common in lactose, fermentable carbohydrate patterns, and certain additive-related complaints. The goal is not to fear every label. The goal is to remove uncertainty hotspots.

- Prefer simpler ingredient panels for trial periods.

- Avoid rotating many new products at once.

- Audit supplements and beverages, not only meals.

- Use one shared household list of “safe defaults” to reduce decision fatigue.

If gluten-related concerns are part of your pattern, this guide on probiotics and celiac-safe selection explains why cross-contact and inactive ingredients matter even when a product looks harmless at first glance.

A diagnostic workup that actually helps starts with triage, not trendy test panels

Many people spend months and significant money on broad “sensitivity” test bundles that do not change treatment. A high-value workup starts with a targeted history: symptom onset, timing window, meal context, repeatability, cofactors (exercise, alcohol, NSAID use, sleep debt, stress), and red flags. From there, clinicians decide whether allergy-focused testing, GI-focused testing, or both are appropriate.

For suspected IgE-mediated allergy, skin-prick testing and serum specific-IgE can be helpful when interpreted with history. These tests are not diagnosis in isolation; false positives and clinically irrelevant sensitization can occur. Oral food challenge remains a key confirmatory tool in selected cases under supervision. For non-allergic symptom patterns, workups may include celiac screening, stool and inflammatory markers when indicated, and targeted elimination protocols.

The most useful question is not “Which test is most advanced?” It is “Which test result will change what I do next?” If a result does not change management, it may not be worth ordering first.

| Scenario | Higher-value initial action | Lower-value common detour | Why this matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid hives, wheeze, throat symptoms after eating | Urgent allergy pathway and emergency plan discussion | Long self-directed elimination before evaluation | Safety risk if severe allergy is missed |

| Chronic bloating and bowel variability | Structured diet/symptom history and GI differential review | Repeated random supplement switching | Improves signal quality and reduces confusion |

| Unclear mixed pattern | Time-boxed elimination plus controlled rechallenge | Permanent broad food restriction | Protects nutrition and long-term adherence |

If you also want strain-level context while you investigate gut symptoms, this explainer on probiotic species and strain evidence helps avoid oversimplified product claims.

A safe elimination and rechallenge strategy is still the most practical tool for many cases

When severe allergy is not suspected and your clinician agrees, elimination and rechallenge can produce better answers than endless guesswork. The key is structure. Eliminate the most plausible trigger set for a fixed window, stabilize routines, and reintroduce one variable at a time with clear observation periods. This is a data collection exercise, not a forever diet.

A workable protocol for adults often looks like this:

- Define one primary symptom target (for example: post-meal abdominal pain, eczema flare frequency, or nasal congestion severity).

- Choose one trigger group to remove first, not five groups simultaneously.

- Hold the elimination long enough to see trend-level change, usually 2 to 6 weeks depending on symptom type.

- Rechallenge with one food at a time in measured portions.

- Track symptom timing across 0 to 48 hours and stop criteria in advance.

What breaks most plans is inconsistency: changing sleep schedule, supplements, caffeine dose, and meal pattern all at once while trying to judge one food. Keep other variables boring. Better data comes from boring routines.

For people building a broader gut-supportive dietary pattern during this process, it can help to compare whole-food approaches such as this probiotic foods guide with your elimination targets so you do not unintentionally remove too much fiber or variety.

Practical note: elimination protocols are not appropriate for possible anaphylactic allergy self-testing at home. If severe reactions are possible, supervised allergy care is the safer path.

Myth vs fact for food reactions: what actually improves outcomes

| Myth | What evidence-supported practice says | Better action |

|---|---|---|

| “If symptoms are delayed, it cannot be food-related.” | Many non-allergic reactions are delayed and cumulative. | Track timing windows, not only immediate reactions. |

| “The bigger the test panel, the better the diagnosis.” | Broad panels often add noise without changing treatment. | Use targeted tests tied to decision points. |

| “More restriction always means faster improvement.” | Over-restriction can worsen nutrition and adherence. | Use time-boxed, focused elimination plans. |

| “No severe reaction means there is no problem.” | Chronic non-severe symptoms can still impair quality of life. | Treat persistent patterns with structured follow-up. |

| “Supplements can replace diagnostic workup.” | Supplements may support routines but do not replace diagnosis. | Confirm mechanism first, then personalize adjuncts. |

The point is not to dismiss supplements or self-management. It is sequencing. Sequence improves outcomes: triage safety first, then mechanism, then strategy.

Children, adults, and aging patterns require different assumptions

Age changes risk patterns. In children, immune development, food exposure timing, and family meal practices can influence presentation and tolerance trajectories. In adults, symptom burden is often amplified by workload, sleep debt, stress, and overlapping GI disorders. In older adults, medication burden, digestive changes, and nutrition vulnerability can make strict elimination harder and riskier if not supervised.

For families, the operational goal is consistency without panic. One kitchen labeling system, one shopping framework, one school or daycare communication template, and one emergency plan if allergy risk is significant. For adults living alone, the equivalent is a short list of reliable meals and products that reduce decision fatigue on stressful days.

If your reaction pattern overlaps with persistent fatigue, mood symptoms, or chronic digestion complaints, review whether your baseline diet quality has dropped during restriction. Over time, inadequate protein, fiber, or micronutrient intake can mimic “new sensitivity” symptoms. This is where periodic nutrition review matters as much as trigger tracking.

When it might be IBS, celiac disease, or another condition entirely

Not every food-related symptom is a primary food sensitivity issue. Some are signals of another condition that needs direct treatment. Celiac disease is one key example: if gluten-related symptoms are suspected, you need proper testing strategy rather than immediate long-term self-diagnosis. The NIDDK celiac resource is a strong starting point for evidence-based patient guidance.

IBS-pattern symptoms can also overlap with perceived food sensitivity. In those cases, targeted dietary strategies and reintroduction phases, often clinician-guided, may be more useful than global avoidance. Meta-analyses on symptom-guided approaches in functional bowel disorders show that individualized reintroduction is critical for sustainability, not just short-term restriction.

This is why diagnosis and management should be iterative. If your initial plan improves symptoms, continue and liberalize carefully. If it fails, escalate evaluation rather than doubling down on more restrictive rules.

- Escalate quickly if there is unintentional weight loss, blood in stool, persistent vomiting, severe fatigue, or nighttime symptoms that keep worsening.

- Escalate if symptoms persist despite a well-run elimination/rechallenge protocol.

- Escalate if your food list is shrinking to the point of nutrition risk.

Build a low-friction food safety system that you can sustain for years

Most people do not fail because they lack information. They fail because the daily system is too fragile. Sustainable symptom control comes from a repeatable workflow you can run under stress, travel, social events, and busy workweeks.

Use a three-layer system:

- Baseline meals: Keep 5 to 7 low-risk meals and snacks that are easy to repeat.

- Shopping filter: Apply one label checklist every time; do not improvise when tired.

- Escalation trigger: Define when you contact your clinician instead of guessing.

Restaurants and travel are predictable failure points. Pre-check menus, call ahead for allergen handling, and keep simple backup foods when needed. Social events are easier when you decide in advance whether you will eat fully, partially, or bring your own option.

This approach protects mental bandwidth. It also reduces the binge-restrict cycle that often follows overly rigid plans. A plan you can repeat at 80% adherence is better than a perfect plan that collapses after one week.

Decision framework: when self-management is enough and when to escalate care

Self-management works best when risk is low, symptoms are stable, and your tracking quality is high. Escalation is appropriate when risk rises, symptoms persist, or data becomes contradictory. You do not need to choose one forever. Move between levels based on evidence from your own symptom trend.

| Current state | Recommended level | Primary objective |

|---|---|---|

| Mild symptoms, no red flags, clear trigger hypothesis | Structured self-management | Confirm or reject one trigger pattern |

| Mixed symptoms, uncertain pattern, partial response | Clinician-guided reassessment | Refine differential diagnosis and testing plan |

| Severe, progressive, or systemic symptoms | Urgent medical escalation | Risk reduction and emergency-safe care |

Long-term success is usually less dramatic than people expect. It is steady symptom reduction, better confidence with food, fewer surprise flares, and less mental load. That outcome comes from method, not from one perfect product or one viral test.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I have a food sensitivity even if allergy tests are negative?

Yes. Negative allergy testing can rule out some immune-allergy pathways, but non-allergic intolerance or broader sensitivity patterns may still explain symptoms. That is why history, timing, and structured rechallenge remain important.

How long should an elimination trial last before I decide it failed?

For many symptom patterns, 2 to 6 weeks is enough to detect direction of change if the protocol is consistent. If there is no meaningful trend and adherence was solid, reassess the hypothesis rather than extending restriction indefinitely.

Should I cut multiple food groups at once to get faster answers?

Usually no. Removing too many foods at once reduces diagnostic clarity and increases nutrition risk. A focused, staged plan provides better data and is easier to sustain.

When should I stop self-experimenting and see a clinician?

Seek clinical review promptly if symptoms are severe, progressive, or include red flags such as breathing issues, significant weight loss, blood in stool, recurrent vomiting, or persistent symptoms despite a structured plan.

Related Articles

- Do probiotics for celiac disease contain gluten? A practical safety-first workflow for supplement label screening.

- Health benefits of probiotic foods and supplements Context on where probiotic foods fit in a broader gut-health strategy.

- Best probiotic foods review Food-first options that can support digestive resilience with less supplement complexity.

- Probiotic strains and species benefits research How to read strain claims without marketing hype.

- How to know probiotic supplements are working A simple framework for tracking meaningful symptom change.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for informational and educational purposes only and is not medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed physician or qualified healthcare professional regarding any medical concerns. Never ignore professional medical advice or delay seeking care because of something you read on this site. If you think you have a medical emergency, call 911 immediately.