Lose Extra Weight and Keep It Off: 20 Evidence-Based Steps

Lose Extra Weight and Keep It Off: 20 Evidence-Based Steps

Reviewed by Dr. Maya Hernandez, MD, MPH (Preventive Medicine)

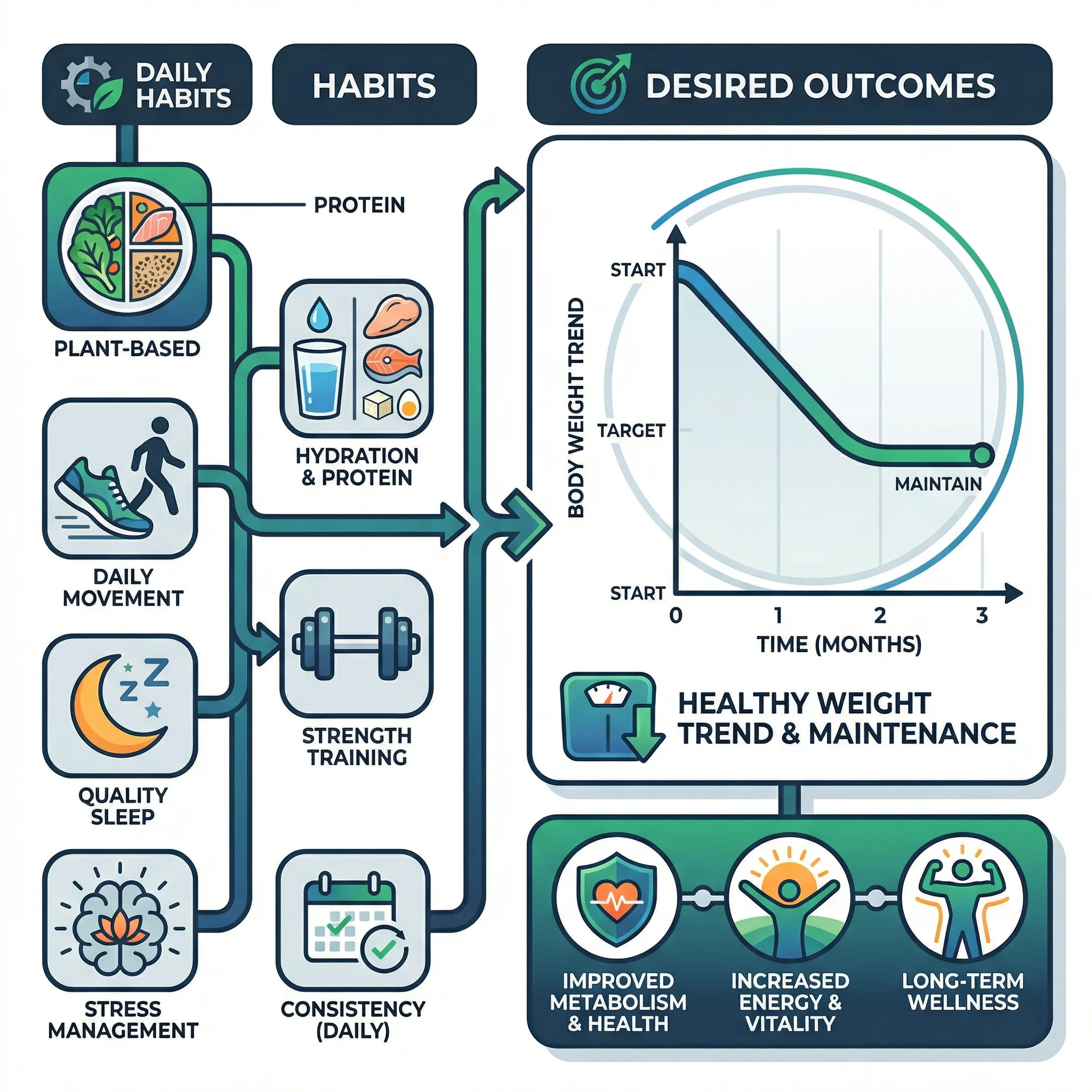

Losing extra weight is hard. Keeping it off is harder. Most people already know that sugary drinks, oversized portions, and inactivity can push weight up over time. The problem is not information. The problem is execution under normal life pressure: long workdays, poor sleep, family schedules, social events, stress, and food environments designed for convenience instead of health. If a plan does not account for those realities, it fails even when the science is correct.

This guide replaces crash-diet thinking with a practical system you can run for months, not days. You will get a 20-step framework that combines nutrition quality, appetite control, resistance training, sleep, stress regulation, and behavior design. The goal is not fast water-weight loss. The goal is steady fat loss, muscle retention, and repeatable habits. We also cover what to do when progress stalls, when to involve your clinician, and how to avoid the all-or-nothing cycle that drives rebound gain.

You can use this article as a weekly checklist. Start with the first five steps, then add more as they become routine. Slow progress is still progress. In obesity medicine, a 5% to 10% reduction in body weight can produce meaningful cardiometabolic improvements, including blood pressure, glycemic markers, and triglycerides (Jensen et al., Circulation, 2014; ADA Standards of Care, 2025).

Quick take: Sustainable weight loss is usually built on a small calorie deficit, high-protein meals, high-fiber foods, resistance training, good sleep, and a home environment that makes better choices easier than default choices.

What changes first when you stop chasing quick fixes?

The first change is psychological: you stop trying to "win the week" and start trying to "win the month." Quick-fix plans typically produce an aggressive deficit, large fluid shifts, and early scale movement. That feels motivating, but it is usually followed by hunger spikes, fatigue, lower training quality, and poor adherence. The cycle repeats: strict weekdays, overeating weekends, guilt, restart.

A better strategy is a moderate and predictable energy gap. For most adults, that means an average deficit of roughly 300 to 500 kcal per day, adjusted for starting size, activity, and medical context. This range is often enough to produce measurable fat loss while preserving training quality and social flexibility. Energy expenditure can adapt downward during weight loss, so your rate may slow over time. That is normal physiology, not personal failure (Hall et al., American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2019).

Another early change is measurement quality. Instead of judging progress from one morning weigh-in, use trend averages and behavior metrics: protein targets met, step goals hit, resistance sessions completed, and bedtime consistency. When behavior improves before the scale moves, you are still on track.

| Approach | Common short-term result | Typical long-term outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Large crash deficit | Fast scale drop from fluid and glycogen | Higher rebound risk, lower adherence |

| Moderate steady deficit | Slower but cleaner fat-loss trend | Better sustainability and muscle retention |

| No structure, "eat healthy" only | Inconsistent appetite and intake | Weight plateaus or gradual regain |

Most people undercount intake, so your food structure matters more than your willpower

Nutrition research repeatedly shows that self-reported intake is often underestimated, especially when portions are not measured and snacks are untracked. That does not mean tracking forever. It means using a short calibration period to learn what your usual meals actually contain. Two to four weeks of structured logging can correct major blind spots, then you can transition to lighter monitoring once your routine stabilizes.

Meal composition is the lever that protects satiety while you reduce energy intake. A high-protein, high-fiber structure can blunt hunger and preserve lean mass during weight loss phases (Leidy et al., American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2015). Start each meal with protein and non-starchy vegetables, then add a controlled carbohydrate portion based on activity level. If your blood sugar is a concern, this framework pairs well with our guide to low and high glycemic index foods and our practical article on diet patterns that help prevent or manage diabetes.

Food quality still matters. Ultra-processed dietary patterns are linked with higher energy intake and weight gain in controlled feeding studies (Hall et al., Cell Metabolism, 2019). You do not need to eliminate every packaged food, but your default meals should be minimally processed and repeatable. For plant-forward options, this companion article on vegan and vegetarian protein sources can help diversify your weekly menu without sacrificing satiety.

| Meal component | Daily target range | Why it helps weight loss |

|---|---|---|

| Protein | About 1.2 to 1.6 g per kg body weight | Supports satiety and lean-mass retention |

| Fiber | 25 to 40 g per day | Improves fullness and meal quality |

| Vegetables and fruit | At least 5 servings per day | Increases volume with lower energy density |

| Liquid calories | Keep near zero when possible | Reduces low-satiety calorie intake |

You can protect metabolism better when walking and lifting are both in the plan

Cardio helps energy expenditure and fitness, but resistance training is the anchor for body-composition outcomes. During a deficit, your body can lose both fat and lean tissue. Strength training plus adequate protein reduces that risk and supports function. Two to four resistance sessions per week is a practical baseline for most beginners. Progressive overload can be simple: more reps, more sets, slightly higher load, or improved range of motion.

Daily movement outside formal workouts also matters. Non-exercise activity thermogenesis, often called NEAT, can vary dramatically between people and between weeks. Step goals are not magic, but they are measurable. If your baseline is 3,000 steps, jump to 9,000 on day one is unrealistic. A better approach is to add 1,000 to 1,500 steps every one to two weeks until you reach a sustainable average.

Exercise quality improves when sleep and fueling are adequate. If you are exhausted, you undertrain and then overeat later. That is one reason integrated plans work better than "diet-only" plans. For broader cognition and exercise adherence context, see our article on physical exercise and brain health.

| Training element | Minimum practical dose | Progress marker |

|---|---|---|

| Resistance training | 2 to 4 sessions weekly | More reps or load at same effort |

| Cardio base | 150 minutes moderate weekly | Lower heart rate at same pace |

| Daily steps | Increase from baseline gradually | Weekly average trending upward |

Your late-night routine can make or break next-day appetite control

Sleep restriction increases hunger signals and can shift food preference toward high-calorie options (Spiegel et al., Annals of Internal Medicine, 2004; St-Onge et al., Sleep, 2016). In practice, poor sleep does three things at once: it lowers impulse control, increases perceived effort of exercise, and raises craving frequency. That combination is brutal for adherence.

Most people do not need a perfect sleep protocol. They need a stable one. Keep wake time consistent, reduce bright light exposure in the final hour, avoid large late meals when possible, and use a repeatable wind-down cue like a shower, light stretching, or journaling. If sleep is currently fragmented, use this related guide on improving sleep habits to build the basics first.

Stress management is not optional either. Chronic stress can push emotional eating, reduce planning behavior, and shorten recovery windows. You do not need to meditate for an hour daily. Even 5 to 10 minutes of breathing drills, a short walk after stressful meetings, or preplanned "if-then" coping scripts can reduce reactive eating episodes.

"Consistency beats intensity" is not motivational fluff, it is physiology and behavior science

When people ask why weight-loss attempts fail, they often focus on metabolism. Metabolic adaptation is real, but behavior volatility is usually the larger driver in free-living environments. Plans that demand constant high effort create frequent breaks in execution. Plans that build defaults survive imperfect weeks.

A default is any pre-decided behavior that removes daily negotiation: same breakfast on weekdays, pre-portioned snacks, grocery list by category, fixed training slots, and a hard cutoff for evening grazing. Defaults reduce decision fatigue and protect results during stressful periods.

The most successful patients in long-term registries tend to share these traits: regular self-monitoring, high physical activity, consistent eating patterns, and rapid course-correction after lapses (Wing and Phelan, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2005). Lapses are expected. Recovery speed is the performance variable.

Myth vs fact: sustainable fat loss is simpler than social media makes it look

| Myth | Fact | What to do instead |

|---|---|---|

| You must cut carbs to lose weight. | Energy balance and adherence drive outcomes more than one macronutrient rule. | Choose a carbohydrate level you can sustain while meeting protein and fiber goals. |

| You should never eat after 6 p.m. | Total intake and meal quality matter more than a fixed clock time for most people. | Set a practical evening boundary and avoid mindless snacking. |

| Exercise alone will remove extra weight quickly. | Exercise supports weight loss, but nutrition structure is usually the primary driver of deficit. | Combine meal planning, strength training, and daily movement. |

| One bad weekend ruins all progress. | Progress is trend-based; two corrective days often recover a lapse. | Return to baseline routine immediately without compensation extremes. |

| Supplements can replace food habits. | No supplement compensates for persistent overconsumption and poor sleep. | Use supplements only for evidence-based gaps under clinician guidance. |

Can 20 practical steps fit into your real week?

Yes, if you stage them. Trying all 20 in a single week is unnecessary. Build layers: measurement and meal structure first, then training and environment design, then advanced adjustments. The list below is written for real schedules and normal obstacles.

- Set a clear 12-week target. Aim for 5% to 8% body-weight reduction, not perfection.

- Establish your baseline. Track morning weight for 7 days and calculate an average.

- Create a moderate deficit. Start near 300 to 500 kcal below maintenance intake.

- Hit protein at every meal. Distribute protein across 3 to 4 meals for satiety.

- Build a high-volume plate. Use vegetables and fruit to control hunger with fewer calories.

- Plan two repeatable breakfasts. Reduce decision fatigue during busy mornings.

- Pre-portion energy-dense foods. Nuts, granola, and spreads should be measured, not guessed.

- Replace liquid calories. Prioritize water, unsweetened tea, or black coffee most days.

- Schedule strength training. Put 2 to 4 sessions on your calendar like appointments.

- Increase steps gradually. Add daily movement until your weekly average is reliably higher.

- Create a post-meal walk habit. Ten minutes after meals can improve appetite control and glucose handling.

- Protect sleep opportunity. Set a consistent bedtime window and pre-sleep routine.

- Install a stress interrupt. Use a short breathing drill before stress-triggered snacking.

- Design your kitchen. Keep visible foods aligned with your plan and hide trigger snacks.

- Build a travel fallback. Predefine convenience meals that still meet protein and fiber goals.

- Review weekly trends. Compare 7-day weight averages, not single-day fluctuations.

- Adjust one variable at a time. If stalled for 2 to 3 weeks, lower intake slightly or raise activity.

- Plan social meals ahead. Decide portions and protein anchors before events start.

- Use rapid recovery after lapses. Resume normal structure at the next meal.

- Reassess every 12 weeks. Move to maintenance phases to preserve results and reduce burnout.

If your default diet quality is currently low, start with whole-food substitutions and simple batch cooking. This companion resource on choosing whole foods can help simplify your first grocery reset.

| Weekly checkpoint | Green zone | Action if below target |

|---|---|---|

| Protein target days | 5 or more days per week | Pre-plan protein for breakfast and lunch |

| Strength sessions | 2 or more sessions per week | Shorten session length but keep frequency |

| Step consistency | Weekly average above your baseline | Add one fixed walking slot daily |

| Sleep window consistency | 5 or more nights on schedule | Set an earlier digital cutoff alarm |

| Trend weight direction | Downward over 2 to 4 weeks | Adjust intake or activity by a small amount |

What should you do when progress stalls for three weeks?

First, confirm whether you are truly stalled. Water retention from sodium shifts, menstrual cycle changes, travel, stress, and hard training can temporarily mask fat loss. Use trend data and waist measurements before changing your plan aggressively.

If the stall is real, use the smallest effective adjustment. Typical options include reducing average intake by 100 to 200 kcal per day, adding 1,500 to 2,500 daily steps, or increasing training volume slightly. Avoid stacking multiple changes at once because you will not know which lever worked.

Medical screening matters for persistent plateaus with strong adherence. Thyroid disease, sleep apnea, medication effects, depression, perimenopause transitions, and insulin resistance can all complicate progress. In some cases, anti-obesity medication can be appropriate as part of comprehensive care; modern trials show meaningful weight reduction for selected patients when combined with lifestyle support (Wilding et al., NEJM, 2021; Jastreboff et al., NEJM, 2022). Medication is not a shortcut. It is a tool that still depends on behavior structure.

How do you keep the weight off after the first successful phase?

Maintenance is not \"stopping.\" It is a planned transition from deficit mode to stability mode. Many people regain because they remove structure too quickly after reaching an initial target. A better strategy is a 6- to 12-week maintenance block where calories rise gradually, training stays consistent, and self-monitoring continues.

During maintenance, keep the same meal templates that worked during fat loss and add calories slowly, mainly from high-quality carbohydrates and healthy fats. If weight jumps quickly for more than two weeks, step back by a small amount and reassess. This process is often called reverse dieting in fitness spaces, but the practical principle is simply controlled refeeding with ongoing measurement.

Maintenance phases also support psychology and performance. Hunger usually settles, gym progress improves, and social flexibility increases. Those benefits make the next fat-loss phase easier if you still have weight to lose. Think in cycles: reduce, stabilize, reassess, then decide next steps. Long-term success usually looks like repeated stable periods interrupted by shorter, intentional fat-loss blocks, not one endless diet.

Frequently asked questions

How quickly should I expect to lose extra weight safely?

For many adults, about 0.25 to 0.75 kg per week is a realistic range after early fluid shifts settle. Faster rates can occur initially, especially at higher starting weights, but slower and steady often predicts better long-term retention.

Do I need to weigh and track food forever?

No. Most people benefit from short calibration phases, then transition to simpler systems such as repeatable meals, hand-portion guides, and weekly check-ins. Re-calibrate temporarily if progress stalls.

Can I still eat favorite foods while losing weight?

Yes. Restrictive all-or-nothing rules tend to backfire. Keep favorite foods in controlled portions and anchor them to meals with protein and fiber rather than eating them as unplanned snacks.

Should I do cardio first or strength first?

If body composition is your priority, schedule strength training as a non-negotiable foundation and layer cardio around it. The exact order is less important than weekly consistency and progressive overload.

What is the most important habit for keeping weight off long term?

Regular self-monitoring. People who maintain loss usually keep some form of ongoing feedback, such as weekly weigh-ins, activity tracking, meal templates, or monthly check-ins, then correct course early when trends drift.

The best weight-loss plan is the one you can still run on a stressful Tuesday

Weight management success rarely comes from a single perfect intervention. It comes from a stack of ordinary behaviors repeated under imperfect conditions. When your system is built around moderate deficits, high-satiety meals, progressive training, sleep protection, and fast recovery from lapses, results become more predictable and less emotionally exhausting.

Use the 20 steps as a living framework. Keep what works, refine what does not, and reassess every 8 to 12 weeks. Your body will adapt, your schedule will change, and your strategy should evolve with it. Sustainable fat loss is not about intensity theater. It is about durable execution.